A Lovely Impressionist Painting

Before commenting on this beautiful, vivid, and joyful Impressionist painting, I would first like to express my sincere thanks to its owner. In a truly constructive spirit — rare enough to be emphasized — this person made a very generous gesture toward the Van Gogh Academy, fully aware that it would in no way influence our opinion on the question submitted to us. We are even pleased to now welcome this individual as a member of our association.

Our independence, it bears repeating, is at the very heart of our identity. It is what allows us to maintain our credibility in a field where financial and historical interests are often in tension. It is also what enables us to navigate the open seas of Vincent van Gogh’s life and work — and beyond that, the era in which he lived.

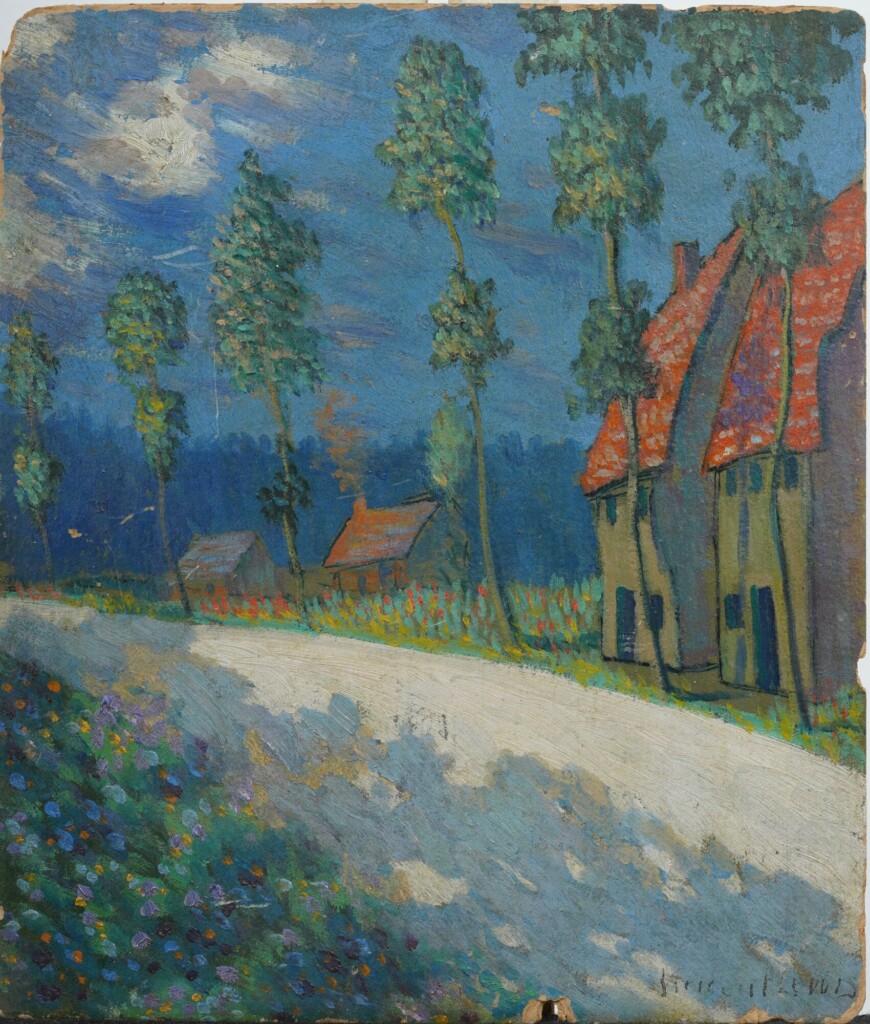

The question we were asked is this: can this work be attributed to Vincent van Gogh? Without suspense, our answer is negative. Below, we outline several arguments that justify this position.

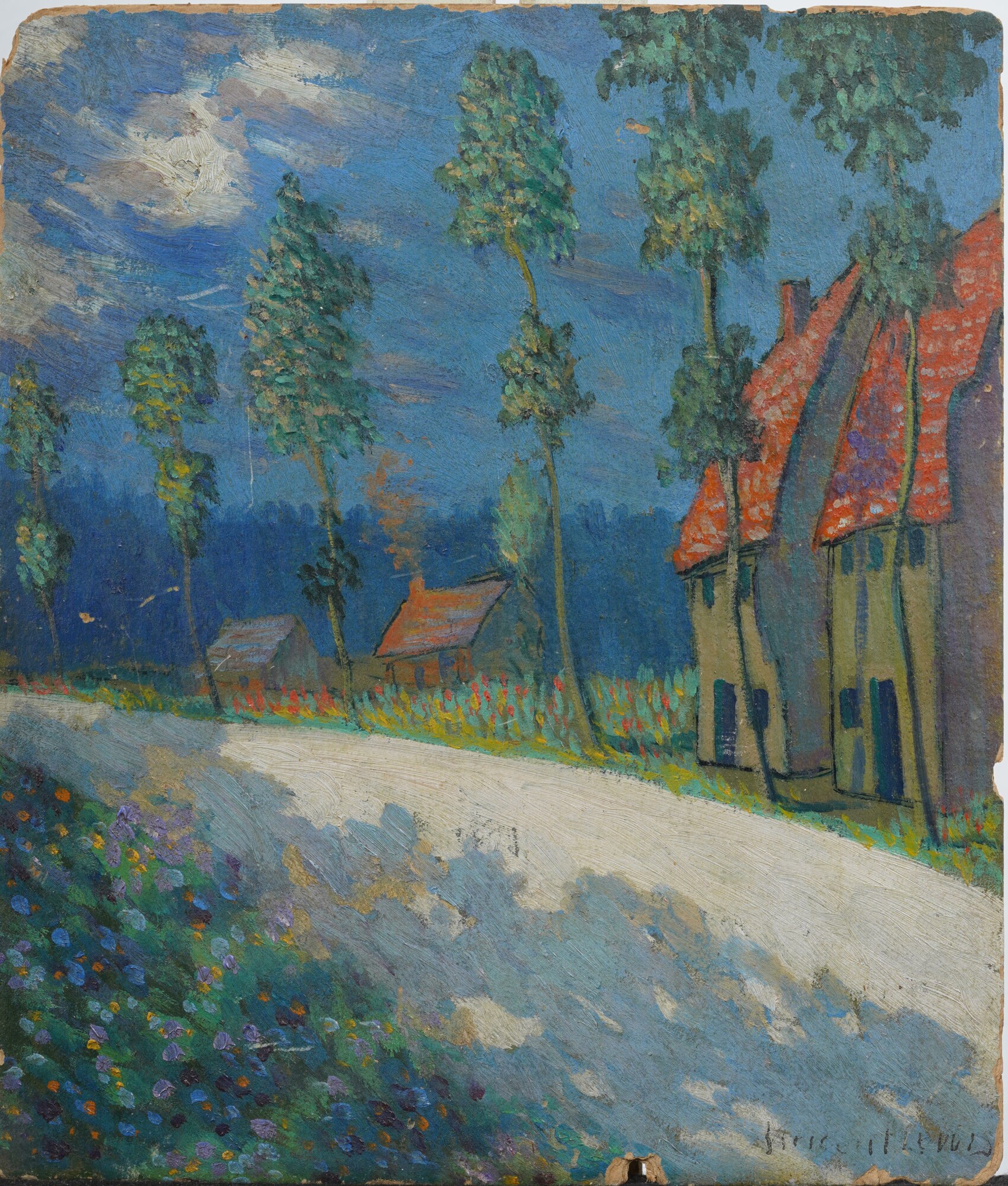

The Support

The photo we received shows that the painting was made on thick cardboard. This was a common support in the second half of the 19th century — easy to carry and handle — and often used by artists such as Cézanne or Toulouse-Lautrec for studies.

Van Gogh only used cardboard during his experimental phases: in The Hague, at the very beginning of his career, and later in Paris, when he was thoroughly reworking his technique and producing numerous floral still lifes in order to master Impressionist colour. But in his later periods — Arles, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and Auvers — we know of no paintings on cardboard.

This is explained by the very clear distinction he made between “studies” and “paintings”: the former being intended for technical exploration and/or artistic exchange, the latter — usually in larger formats — intended for the art market. In both cases, cardboard was unsuitable. Van Gogh was committed to improving his oil painting on canvas, a noble support suited to both artistic ambition and commercial exchange. Cardboard did not serve this purpose.

One might be tempted to think that he could have used cardboard for financial reasons, since it was cheaper than canvas. But as he was generously supported by his brother Theo, the painter was not short of money in the final years of his life. He did sometimes manage his income poorly, but never to the point of being forced to paint on whatever he could find. When he ran out of canvas, he preferred to draw. And on the one known occasion when he truly lacked canvas — in Auvers-sur-Oise — he chose to paint on café dishcloths instead.

Finally, the cardboard presented here appears quite fresh. Those I have seen from the late 19th century are generally darker and more visibly aged.

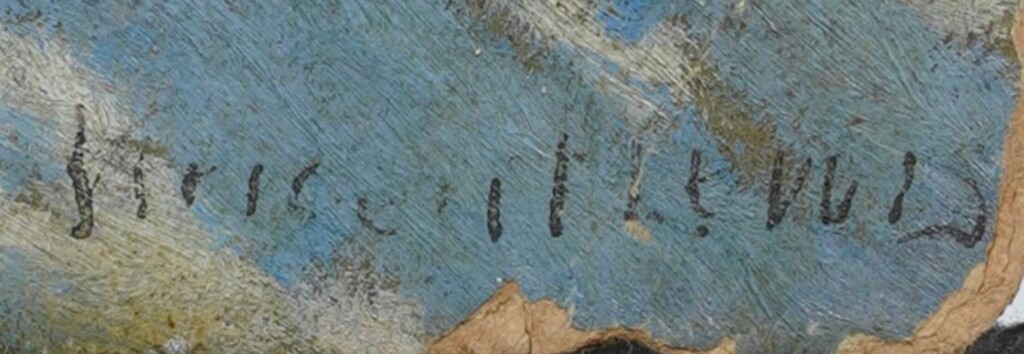

The Signature

One would have to be in very bad faith not to read “Vincent” here. However, what follows is more ambiguous. Our interpretation is “Levois,” but we have not identified any artist by that name whose existence could help clarify the attribution of the work. What distances this painting even further from a Van Gogh attribution is the fact that he very rarely signed small-format studies, and never added anything to his signature.

The Painting

We understand that, in combination with the signature, this work may evoke Van Gogh. The use of complementary colours is well handled, particularly in the lower part. The bluish shadows tinged with yellow cast across the path, and the cheerful flowerbed in the foreground on the left, show a fine level of control. The chosen angle also shares some features with Van Gogh’s practice, as he liked to look at what lay at his feet as much as he liked to look into the distance, allowing the viewer to explore the scene or landscape with a pleasing sense of depth.

However, when it comes to the definition of the brushwork — which is too vague when suggesting flowers, foliage, or the edge of a forest in the background — we are clearly not within Van Gogh’s visual vocabulary. As for the drawing of the rooftops and buildings, it is far too naïve to be from the hand of the master. The architectural style, moreover, appears nowhere along Van Gogh’s path. We do not know of this type of house in Provence.

Their position is also odd. Very close to the road, with no alley, garden, or fence, they seem more the result of imagination than of observation. But Van Gogh always observed his subjects with great patience.

Does all this make it a bad painting? Certainly not. It is lively, fresh, and quite charming in its naivety, and it shows a fair degree of control. But if we had to date it, we would lean towards the first half of the 20th century, rather than the 19th. It deserves to be cleaned, framed, and can brighten a light-filled interior. But unless a prestigious author other than Van Gogh — who has no connection to this painting — can be identified, this is not a museum piece.