Fake Van Gogh or Genuine Copy? The Strange Case of a Copy of Eugene Boch’s Portrait

For the past twenty years, I have received authentication requests almost every week. Sometimes two, sometimes five, sometimes none. But on average, I would say around a hundred per year. Most of the time, when people approach me with a minimum of courtesy, I reply and give my initial impression – quickly, with no commitment on either side – and I make it clear that my opinion has no legal or financial value.

I have never charged a cent for these opinions, which I intend to be helpful – though they are sometimes poorly received. I understand that. People think or hope they have found a treasure, only for some stranger to tell them they have found nothing at all. I also understand that my opinions are not always accepted at face value and that some people resist my conclusions. In the end, it changes nothing for me – the only true judge in these cases is the market.

There have been two or three times when I initially hesitated over a submission, but that hesitation never lasted. Still, I would love to be involved in the discovery of a lost Van Gogh!

With the founding of the Van Gogh Academy, I came up with an idea to settle disputes: for those who submit artworks for authentication, I offer to publish a short article about their discovery on our website. In these articles, I present the reasoning behind my opinion, along with an image of the submitted artwork. This way, anyone can form their own judgment based on the available evidence.

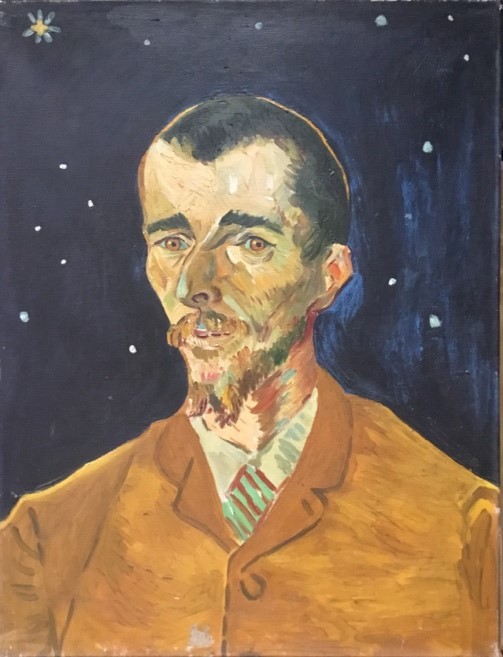

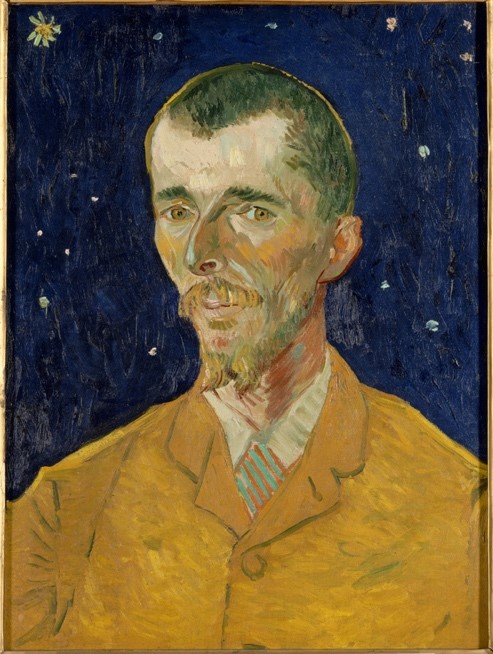

Since I started offering this approach, I have only received one acceptance – for a particularly interesting painting, the subject of this first article: a copy of a famous portrait that Van Gogh titled The Poet. This is a major piece in Van Gogh’s œuvre – it contains his first starry sky and is a portrait that is not truly a portrait. Like La Berceuse or Dr. Gachet, the painter was not trying to depict a person, but rather an idea. In this case, Eugène Boch is playing a role –that of an idealized poet, with refined and noble features, marked by humility, whose mind escapes into the infinite depths of the firmament. I will return to this idea later, but this painting demonstrates that Van Gogh was, above all else, a symbolist of reality.

Van Gogh and Eugène Boch

The Dutchman met Eugène Boch in early July 1888, likely during one of his excursions to Fontvieille, a picturesque village a few kilometers from Arles. He describes his encounter with the Belgian artist in a letter to his brother Theo:

“This Bock stays with McKnight and seems to be working hard. But I haven’t seen anything yet. He’s a young man whose appearance I like a lot. A razor-sharp face, green eyes, with a certain distinction. McKnight looks very vulgar next to him.” Arles, July 9, 1888

The next day, still under the impression of their meeting, he adds:

“This Bock has a bit of the look of a Flemish gentleman from the time of the Compromise of the Nobles, in the era of the Silent and Marnix. It wouldn’t surprise me at all if he turned out to be good.”

Less than two months later, on September 3, Van Gogh had completed his portrait and recommended that Theo welcome Boch warmly during his upcoming visit to Paris:

“You’ll soon see this young man with a Dantesque look, as he’s coming to Paris, and by lodging him, if there’s space, you’ll be doing him a favor. He has a very distinguished appearance, and I believe he will become so in his paintings as well. He loves Delacroix, and we had a long conversation about Delacroix yesterday – he was already familiar with the violent sketch of Christ on the Sea of Galilee.

Well, thanks to him – I finally have the first sketch of that painting I’ve been dreaming of for so long – The Poet. He posed for it. His delicate face with green eyes stands out in my portrait against a deep ultramarine starry sky; his clothing is a small yellow jacket, an ecru linen collar, and a multicolored cravat. He gave me two sittings in one day.”

Boch, with his Dantesque appearance, his Flemish gentleman air, his distinguished look, and his refined features, was the perfect subject for The Poet. And let’s note in passing how often the titles of Van Gogh’s works diverge from the artist’s own intentions – but we’ll return to that!

A Lost Painting?

The painting ended up in Boch’s collection and remained there until 1941, when it was donated to the French state. I have not been able to determine when Boch acquired it or from whom – was it Theo? His widow Johanna?

Van Gogh describes the painting twice in his letters. The first time, on September 3, he refers to it as a “sketch” for which Boch sat twice. We can reasonably assume that this sketch was quite advanced. However, when he mentions it again on September 8, the wording is more ambiguous:

“The Night Café continues, along with The Sower, and also the heads of the old peasant and the poet – if I manage to complete the latter.”

So as of September 8, the painting was still unfinished – somewhat surprising, given that Van Gogh rarely left paintings on his easel for four or five days. However, we must consider an unexpected disruption: following a conflict with his landlord, Van Gogh spent three days and nights painting The Night Café. Once it was finished, and the dispute settled, he could return to his planned work.

This brief delay led some to speculate that there might have been two versions of The Poet—a preliminary study and a more refined painting that has since disappeared. In this context, the appearance of a second version in 2025 seems plausible – perhaps the lost version has been found!

A Copy, Not a Van Gogh

However, the painting that resurfaced a few months ago has an inscription on the back, barely legible: “P. Alexandre / 1903.” The only contemporary P. Alexandre I could identify was an honorary Belgian inspector, with no known connections to painting. In 1903, the painting was likely still with Boch – in Belgium, yes, but out of public reach. Could P. Alexandre have been acquainted with The Poet’s model and, inspired, attempted a copy?

Or perhaps the inscription refers not to the date of execution, but to a later acquisition? Could the copy predate that inscription? Or is it merely an error? We cannot say for certain.

What I am fairly certain of, however, is that this is not a Van Gogh. The Dutchman did make replicas to gift to his models, but these were not mere copies – he always introduced variations. That is not the case with this Poet copy from 2025. The stars are in exactly the same places, and there is an evident effort – sometimes unsuccessful – to replicate the exact flesh tones, folds of fabric, and lighting effects of the original.

But not just anyone can be Van Gogh. Where the master sculpted his material – even in flat areas – to enhance movement and volume, the copyist, though skilled, merely spread paint on the canvas. Where Van Gogh’s lively, assured brushstrokes created the effect of a beard, the play of light on skin, or hair falling on the forehead, the copyist carefully applied small, cautious strokes in an attempt to mimic the original – without success. The drawing is weaker, and despite closely following the original’s composition, the copy feels limp. Van Gogh’s Poet conveys a sense of uprightness and elevation; the copy portrays a somewhat dazed figure, slightly slumped, with drooping features. Finally, the copy’s sky was painted using black – precisely what Van Gogh sought to avoid.

All these small details, taken together, make an attribution to Van Gogh completely impossible in my view. However, this is not a forgery.

A forgery is defined by an intent to deceive, which is not the case here. The owner came forward with no pretense, and their painting’s history contains only one common trait of forgeries – the ambiguous reference in correspondence, often a starting point for fraud. But in this case, it’s not decisive, and the penciled inscription – easy to erase – would never have been added or preserved by a true forger.

The fact that it remains is evidence of the owner’s scrupulous honesty. They can take pride in possessing a fine, likely old copy – and a lovely mystery.

Wouter van der Veen